Larry L. Boleman, Dennis B. Herd and Chris T. Boleman

Download the PDF | Email for Questions

Animal Selection | Ideal Market Steer | Feeding Suggestions | Nutrients and Requirements | Types of Feed | Supplements and Additives | Digestion and Physiology | Starting Cattle on Grain | Types of Diets or Rations | Diet Formulations and Examples | Management of Feed | Feeding Commercial Steers | Health Management | Metabolic Disorders | Other Problems | Handling Calf | Preparing for Show | Management Calendar | Knowledge and Skills

There’s a lot you need to know if you’re going to raise beef cattle to exhibit at shows. Your first job is to decide what kind of beef project you want to undertake. There are four types of beef projects to consider:

- Haltered market steers

- Haltered breeding heifers

- Commercial steers

- Commercial heifers

Of those, haltered show steers and heifers demand the most time, expense and work. This publication will focus mainly on these projects, with some references to commercial projects.

Commercial steer and commercial heifer programs are outstanding beef training projects. They teach you about economic strategies to feed and develop animals for market or for commercial cow-calf production. These projects place more emphasis on feed costs, average daily gains, feed conversions, and management strategies such as dehorning, castration and vaccination. Participants often must keep a detailed record book and undergo an interview to complete the project. Commercial cattle are not trained to lead or show by halter, but are instead maintained in a pen. They are eventually evaluated as a pen rather than as individuals.

More information on commercial cattle projects can be obtained from your county Extension agent.

Animal Selection

After you decide on the type of project, you need to select the project animal. This is not an exact science, but practice, patience and experience will help you select the right steer or heifer. It is a good idea to evaluate several young animals before deciding on one.

Just as important, you should ask someone else to accompany and help you during this process. Usually, county Extension agents, agricultural science teachers, ranchers, breeders and experienced exhibitors offer the best advice.

There are selection criteria each 4-H member should consider when choosing haltered market steers and heifers for show. Whether your project is a steer intended for market or a heifer intended for breeding, both projects must meet many of the same criteria. After you have selected your project, but before you buy an animal, talk to your county Extension agent about county, regional, state or national rules governing project exhibition. The rules regarding animal age, frame size, weight and breed must all be coordinated for specific shows and show dates.

You need to decide in which show or shows you will enter your project. Study the rules of the intended show carefully for specific guidelines. These rules will dictate ownership dates, minimum and maximum weights and ages, and class weight divisions. Base your selection of animals on the criteria of age, weight, frame size, and breed or breed types.

Age — Actual age and birth date are very important. Steers and heifers are placed on feed between the ages of 6 to 10 months. Most calves are weaned at about 6 to 7 months old. Steers can reach the correct weight for slaughter (slaughter point) between 14 to 20 months old. Heifers reach puberty to breed between 14 to 16 months old. Most steers are exhibited at 16 to 20 months. Heifers may be shown to 24 months old, and some breed associations even allow mature cows to be shown. Be sure to check the breed association requirements and fair rules and regulations.

Weight — For show, haltered steers and heifers are expected to attain a specific weight range, based on age and frame size. You will need a good calendar and some math skills to chart the date of birth and show dates and to compute the beginning weight at weaning (or purchase), days on feed and show weight.

A steer to be exhibited at major shows in winter or spring (January to March) is normally placed on feed in March to May the previous year when it weighs about 400 to 600 pounds. This weight should allow the steer to reach 1,100 to 1,300 pounds in January. (This weight allows for reduced weight gain and shrink because of training, fitting, conditioning and hauling.)

Show steers normally are on feed about 270 days and gain between 2.0 and 3.5 pounds a day. This rate of gain and growth can be controlled slightly for faster or slower gain by regulating the feed ration and amount fed.

Begin to look for and buy calves in March, and complete your selection by the end of June. Your date of purchase is your “beginning on feed date,” about 6 to 7 months after birth. Also, most ownership or validation deadlines for major shows occur before July 1. These calves should have been born in August, September, October, November and possibly as late as December and January to make the major shows held in January, February and March of the next year.

Beginning weight 400 to 600 pounds

Days on feed About 270 days

Average daily weight gain 2.0 to 3.0 pounds

Total weight gain 550 to 800 pounds

Final show weight (March) 940 to 1,410 pounds

A range of possibilities exists. However, 940 pounds may be too light to make the minimum weight limits at some shows, and many judges may consider 1,410 pounds to be too heavy to be competitive. Some cattle will need to gain faster and others will need to have limited feed intake to reach the desired or competitive minimum or maximum weight goals.

Let’s look at an example: A 600-pound calf placed on feed in July gains 2.85 pounds a day for 250 days. This equals 700 pounds of total gain. This calf would have a 1,200- to 1,250-pound final show weight.

Frame Size — Frame size, or height in relation to weight, is another important selection criterion. Frame size generally is associated with growth and can be used to predict the final height that correlates with a mature weight range. On average, steers grow about 3/4 inch per month from weaning to finishing. Weight gain ranges from 2.0 to 3.5 pounds per day. You can predict the final height of a steer on the date of the show by knowing the exact age and height of the animal at any given time it is on feed.

Table 1 is an example of a beef steer growth chart from the purchase date to the show date of the project. Refer to the Table 2 Frame Chart, simply match up the age in months with the hip height in inches. The most popular frame sizes are 4 to 6 for ideal show cattle height on show day.

Table 1 is an example of a beef steer growth chart from the purchase date to the show date of the project. Refer to the Table 2 Frame Chart, simply match up the age in months with the hip height in inches. The most popular frame sizes are 4 to 6 for ideal show cattle height on show day.

Most judges prefer that a live market steer weigh between 1,100 to 1,300 pounds. A steer with a frame score below 4 is too small, while one with a frame score above 6 is too large for most judges. Steers with frame scores of 3 and 7 might be acceptable to some judges if the steers are managed, fitted and exhibited properly and if they excel in visual and carcass characteristics.

Breeds — There are several breeds to consider when selecting a market steer or breeding heifer. Always  check the show rules for classification and breed class. In many shows, especially at the county level, there are generally three divisions for breed types: British, Continental and American breeds. In most major shows, these divisions are further divided into the most popular breeds:

check the show rules for classification and breed class. In many shows, especially at the county level, there are generally three divisions for breed types: British, Continental and American breeds. In most major shows, these divisions are further divided into the most popular breeds:

✦ Purebred British Breeds: Angus, Red Angus, Hereford, Polled Hereford and Shorthorn. These breeds are typically more easily fattened or finished; they usually have a more docile disposition; and the average breed size is smaller than the other groups. They are typically smaller, are easier to handle and are recommended for younger and less experienced cattle exhibitors for beginning projects.

✦ Crossbred or Purebred Continental Breeds: Charolais, Chianina, Limousin, Maine Anjou, Simmental, and Any Other Breed (AOB) or crosses. Some examples of other breeds are Gelbvieh, Braunvieh and Salers. These breeds are often referred to as “Exotic” and are larger, fast growing and more muscular, and have less fat. Because of their larger size and fast growth pattern, they are recommended for older, stronger and more experienced exhibitors.

✦ Crossbred or Purebred American Breeds (Biological Type): Brahman, Brangus, Santa Gertrudis, Simbrah, and American Breed Crosses (ABC) such as Bralers, Brahmousin, Beefmaster and any other crosses with Brahman breeding. These breeds with Brahman or Bos indicus breeding generally perform more efficiently in hot, humid climates.

Evaluate all four criteria thoroughly before selecting your project and animal. Be sure you have a clear understanding of the evaluation criteria the judge will be using to select the “ideal” market show steer or heifer. Then begin your feeding and management program.

Ideal Market Steer

Every market steer in the show ring is evaluated for its end product using the grade standards for quality and yield as set by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). The U.S. commercial beef industry—uses two grading systems—one predicts lean quality, the other predicts carcass yield to determine carcass value. These also are the evaluation criteria that the judge will use at show.

USDA Quality Grades — By far the most difficult standard to predict accurately in a live animal is the USDA Quality Grade. Quality grade in young cattle (under 30 months old) is basically determined by the total amount of intramuscular fat, or marbling, in the ribeye. Besides marbling, other factors associated with quality grading include predictors of maturity, texture, firmness and color of lean. Although maturity is an important factor, show steers for slaughter are usually less than 2 years old, so maturity is not critically evaluated in the live steer.

Assuming A maturity, the quality grades in order of the most to least marbling scores are Prime, Choice, Select, and Standard. A realistic goal for you to achieve in your steer is USDA Choice Grade.

A judge can use only visual characteristics of external fat deposits to estimate quality grades. The rule of thumb: A steer that possesses a uniform degree of finish, measured at 0.35 to 0.45 inch of fat over its rib cage, grades Choice if breed genetics, frame size, weight and age criteria are correct.

USDA Yield Grades — Yield grades are used to estimate carcass cutability or percent lean yield. Cutability is the percentage of bone-less, closely trimmed retail cuts. Basically, less fat and more muscle equals higher cutability. Cutability and numerical yield grades (USDA YG 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5) have an inverse relationship: the higher the cutability, the lower the numerical yield grade. USDA Yield Grade 1 is much leaner than USDA Yield Grade 5.

Four measured factors are used to formulate yield grades: fat thickness, ribeye area, carcass weight, and kidney, pelvic and heart fat. The numbers used to derive yield grades will follow the description of all the measurements.

Fat thickness (FT) is measured between the 12th and 13th ribs, opposite the rib eye and is the major factor when figuring yield grades. Fat thickness measurements usually range between 0.1 and 1.0 inch. This measurement can also be adjusted according to other locations of fat deposits. Some common deposits include the brisket, chuck, round and cod fat. A measurement of 0.4 inch is considered to be well finished but not too fat.

The ribeye area (REA) is measured using a grid. The measurement is taken between the 12th and 13th ribs and may not be adjusted for any reason. Ribeye areas are measured in square inches and range from 10 to 17 square inches. The average steer has about 1.1 square inches of ribeye for every 100 pounds of live weight. An average 1,200-pound steer has a ribeye area of about a 13.2 square inches.

Steers with more muscling have larger ribeyes, but ribeye area measuring more than 15.5 square inches is considered too large. Cuts that are considered too large are extremely challenging to market and cause problems with marketing when placed in a retail case.

The hot carcass weight (HCW) is also a fixed variable and may not be adjusted. Light and heavy carcasses both are price-discounted severely. This is the reason steers weighing less than 900 pounds or more than 1,300 pounds are sometimes evaluated harshly in the show ring.

An average dressing percent for slaughter steers is 63.5 percent. Multiply the weight of a live steer by the dressing percentage to get the resulting hot carcass weight (1,300 pounds x 63.5 percent = 826 pounds). This weight is still acceptable. However, as carcass weight exceeds 850 pounds, beef cuts become too large to market efficiently.

The final factor is kidney, pelvic and heart fat (KPH). This is a measurement of the internal fat surrounding vital internal organs. KPH is a numerical percentage representing the weight of the kidney, pelvic and heart fat as a percent of the carcass weight. KPH usually ranges between 1 to 6 percent. KPH is very difficult to predict in live cattle, but variation among beef cattle is minimal. Most range between 2 to 3 percent.

In feeding your show steer to obtain the desirable ideal carcass, remember these points:

✦ Try to select a calf with more than adequate muscle shape to ensure an average or better REA (12 to15 square inches).

✦ Feed to produce a fat cover of 0.35 to 0.45 inch. This should result in USDA Yield Grade 2 and the Choice grade if genetically possible.

✦ Aim for a show weight of 1,150 to 1,275 pounds. Refer to the growth chart for exact age and height measurements to predict approximate final height and weight.

If you follow these guidelines, your market steer should be in an excellent position at show for carcass acceptability from both USDA Quality and Yield Grade evaluations.

Feeding Suggestions

Feed costs are a large but necessary expense in managing beef cattle for show. An adequate amount of a properly formulated diet or ration is essential to develop the genetic potential of show cattle. You need to be familiar with the basic principles of nutrient requirements, nutrient composition of feeds, digestive physiology and diet formulation.

You also must observe your animals closely, recognizing their habits, likes and dislikes; complete tasks in a timely manner; establish routines; and recognize normal from abnormal behavior. Such observations and actions will help you detect problems early so they can be corrected before they become serious and costly.

Nutrients

Nutrition is the process by which animals consume, digest, absorb and use their food for either maintenance activity, growth, fetal development or milk production. The components of food or feed with similar chemical properties and/or similar physiological functions in the body are referred to as nutrients. Protein, minerals, vitamins, water, sugar, starch, cellulose and fat are nutrients. Sugar, starch, cellulose and fat are referred to as “sources of energy,” and required amounts of energy are needed for certain functions.

Nutrients and Requirements

The amounts of each nutrient needed by cattle for various levels of performance have been determined by years of research. The National Research Council publishes them regularly. These published requirements are very accurate for groups of similar cattle, but may be slightly high or low for individual animals. Thus, if an individual animal is not performing well, consider increasing the protein, mineral and vitamin levels in the diet by a reasonable amount.

The concentration of nutrients in feeds and the concentration needed in the diet are commonly expressed as a percentage of the diet consumed at a predictable level. However, remember that cattle require an actual amount (weight) of various nutrients, not some percentage or proportion. So, consider the percent of nutrients in the diet as a feeding guide only when feed intake is within a normal range.

Measures of energy content or requirement are expressed as percent TDN (Total Digestible Nutrients) or as NEM (Net Energy of Maintenance) and NEG (Net Energy of Gain). Both are measured as Mega calories (Mcal) per pound or 100 pounds of feed.

The dry part of a feed, not the moisture, contains the nutrients. Most dry feeds contain 7 to 13 percent moisture. Molasses is 25 percent water. To standardize values, nutritionists usually adjust nutrient requirements and feed composition to a complete dry matter basis. However, feed tags express nutrient content on an as-fed basis, not dry basis. It is important to know the basis on which nutrient values are expressed when you are reviewing information and making comparisons.

Types of Feed

Types of feeds used in rations are classified as grains, roughages, protein, concentrates, minerals, vitamins and additives.

Grains — Feeds high in energy will fatten cattle. Corn is the best fattening grain because it is more consistent in nutrient content and processing properties, but in any diet it may be replaced pound-for-pound by sorghum grain.

Barley may replace up to 50 percent of the corn or sorghum grain in a ration. Some feeders use barley products because they think it produces finish on the steer that is more appealing in its handling properties. Handling qualities are defined by the smoothness of finish a market steer possesses over its rib cage.

However, water consumption, which affects the moisture content of tissues, has a much greater effect on handling qualities. Also, calves experience less bloat on corn diets than on high barley diets. High percentages of grain, up to 65 percent, will be included in finishing rations. Wheat is a good high-energy feed, but is not recommended in show diets because of its rapid digestion and tendency to cause acidosis (see the section on health).

Oats are excellent for growth and development of steers or heifers. A mixture similar in nutrient content to oats can be formulated with a high-energy source such as corn, a roughage source such as cottonseed hulls, and a high protein source such as cottonseed meal. A mix of 70 to 75 percent corn, 15 to 20 percent cottonseed hulls, and 10 to 15 percent cottonseed meal is about equal to the nutrient content of oats. Such a mix normally is less expensive to feed and just as effective in growing steers or heifers.

Energy density of the diet, not the type of feed (corn vs. oats), is the dominant factor controlling rate of gain and degree of growth and fattening. Lean tissue development is maximized when daily rates of gain are less than 2.25 pounds. Fattening is increased proportionally to rates of gain above 2.25 pounds.

Feed only quality grain. Avoid weevil-eaten, dusty and spoiled feeds. Grain should be processed. Steam flaking, rolled, cracked or coarsely ground grain is preferred. Dusty, powdered feeds reduce intake and result in more digestive disturbances. Whole shelled corn is preferred to powdered corn. Sorghum grains must be processed. Calves weighing up to 450 pounds can digest whole kernel grains satisfactorily. For cattle above this weight, all grains should be processed, except for whole shelled corn, which is discussed later in the section on commercial steer feeding programs.

Protein supplements — Feeds such as cottonseed meal, soybean meal and linseed meal increase the protein content of the diet. Small amounts (less than 3 percent) of fish meal, dried blood meal, corn gluten meal, linseed meal and brewers or distillers grains can be used to improve the amino acid balance of the diet and the supply of amino acids to the lower gut because they contain more rumen escape protein. Overuse of this latter group can result in a lack of adequate rumen degradable protein, and the animal proteins are not palatable, which limits their use.

Young, lightweight cattle need higher concentrations of protein in their diets than older, heavier cattle. Adequate levels of protein are critical for digestion, maintenance of feed intake and lean growth, but the feeding of excess protein is expensive, can cause more heat stress and may result in more digestive problems.

Urea can substitute for natural protein in high corn diets for heavy cattle (greater than 800 pounds); commercial steer feeders will want to take advantage of this cost-cutting substitution. However, show steer feeders prefer the extra bloom that comes with natural proteins. Light-weight cattle (less than 600 pounds) must have natural protein because they cannot use urea to meet their total protein supplement needs.

Roughages — Cottonseed hulls are the most satisfactory roughage. Cottonseed hulls have low nutrient value, but cattle like them. This helps

Roughages — Cottonseed hulls are the most satisfactory roughage. Cottonseed hulls have low nutrient value, but cattle like them. This helps

keep them on feed. Hulls also help hold the feed mix together, preventing

feed separation.

A small amount of dehydrated alfalfa pellets adds the nutritional quality lacking in cottonseed hulls. Although peanut and rice hulls are cheaper roughage, they are not recommended for show cattle.

A small slab (3 inches or less thick) of medium-quality grass hay daily will help keep calves on feed by reducing the chances of digestive upsets. In finishing diets, a small amount of hay is recommended for the physical properties it adds to the diet and not its nutrient contribution; thus, medium quality hay works better than poor or excellent quality.

Hay is your insurance measure when feeding cattle. At the first sign of any digestive problems, increase hay while reducing concentrate. Once the problem is corrected, gradually decrease hay while increasing concentrate, but do not try to eliminate all hay, because this greatly increases the likelihood of nutritional ailments of acidosis, bloat and possibly founder.

A big full middle on a steer can be more effectively controlled by limiting feed and water the last few weeks before show, not by eliminating hay from the diet. Hay should be free of mold, dust and bad odors. Alfalfa hay is nutritious but increases the odds of bloat.

Other feeds — Molasses helps prevent feed separation and settles dust in the mixed ration. Because molasses is mostly sugar and is rapidly digested, using more than 3 to 4 percent can increase the chances of acidosis and bloat.

Wheat bran adds variety to the ration and is somewhat laxative, thus making a good conditioner, if needed. Fats and oils also settle dust and increase the energy content of diets. Fat sources include whole cottonseed, beef tallow, corn oil, soybean oil and commercially manufactured protected fats.

Supplements and Additives

Vitamin A — Feedlot cattle require 1,000 International Units (IU) of vitamin A per pound of feed. Green pastures normally supply adequate vitamin A. Green hays can be low in vitamin A because it deteriorates during storage.

Because it is inexpensive and subject to loss during storage, add supplemental vitamin A to the diet at two to three times the IU requirement. Vitamin A toxicity can result when vitamin A is fed at 20 to 30 times the requirement.

Vitamin D — Texas cattle that are outdoors and exposed to sunlight receive ample vitamin D. However, sheltered cattle should be supplemented with at least 125 IUs per pound of feed. Although cattle can tolerate up to 11,000 IUs of vitamin D per pound of feed for short periods, it is not considered safe to feed more than 1,000 IUs for extended periods.

Vitamin E — Vitamin E requirements are not well established, but are considered to range from 5 to 30 IUs per pound of feed. Cattle can tolerate up to 20 times the requirement. Because of its antioxidant properties, higher levels of vitamin E (500 to 1,000 IUs per head per day) are known to reduce sickness in receiving cattle, decrease stress from toxins like gossypol, and improve meat color and shelf life of retail case beef.

B-Complex vitamins — These vitamins are normally synthesized by rumen microbes in adequate amounts and do not need to be added to the ration. However, high levels of antibiotics, acidosis and other rumen-induced factors may reduce microbial growth and result in a deficiency. Thus, spot B-complex supplementation during times of stress may be beneficial. For quick action, injectables are preferred. Follow the directions on the product used.

Minerals — Minerals are required for structure (hooves, bones and teeth) and regulation of physiological processes in the body. Highgrain diets are deficient in calcium, salt and certain trace minerals. High-phosphorus supplements, which are recommended for cows on forages typically deficient in phosphorus, are unsuitable for cattle on high-grain diets.

Feed-grade limestone and oyster shell flour are good sources of calcium; dicalcium phosphate and defluorinated phosphate are good sources of calcium and phosphorus. Adequate copper, zinc and selenium are required for good health. Rations should be fortified with all needed minerals in order to maintain top level performance and health. Salt should be available free-choice (all they want) at all times.

Antibiotics — Antibiotics such as Aureomycin, supplied in the feed mixture at 10 to 15 milligrams daily per 100 pounds of live weight, can prevent some feedlot stress problems. This low-level feeding will help control low-level infection, but has little effect on increasing weight gain.

Some people do not put antibiotics in the feed. They believe that medicine is more effective when used at treatment levels for a specific problem rather than when used in prevention levels in feed. Usually, antibiotics are used in receiving rations for young cattle going on feed for the first time and are eliminated after a few weeks. It is important not to use antibiotics (feed additives or injectables) too close to the time of slaughter. Follow instructions and withdrawal times for the product used.

Growth promoters — Growth implants, which are placed under the skin on the backside of the ear, increase the rate and economy of gain. Because implants tend to reduce fat deposition and increase lean muscle growth, the carcass quality grade may be lowered very slightly.

Because sunken loins and raised tail heads are often noticed in implanted cattle, implant only those show cattle whose appearance will be enhanced by such effects. General appearance is of more value than maximum efficiency in show cattle. However, commercial feeding projects should emphasize implanting and efficiency.

Implants must be used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations; various restrictions exist on the time of slaughter after implanting. Implants for bulls or heifer replacements are not recommended.

Ionophores — Several feed additives, collectively referred to as ionophores, improve feed efficiency when added to the diet as recommended by manufacturers. In addition to improving feed efficiency, the products vary in their capacity to suppress or control acidosis, bloat and coccidiosis.

An ionophore is definitely recommended in both show and commercial steer diets. Many feed companies make diluted carriers that can be added to home mixes safely. Some ionophores are extremely toxic to horses, so feed only to cattle and at the rates recommended for the product used.

Buffers — If feeding high levels of grain causes acidosis, it would seem that a buffer such as sodium bicarbonate would be useful as an additive to the diet. A buffer can be useful during the transition period from forage to grain diets or following a bout of acidosis and off-feed.

However, cattle produce enough of their own natural buffers once they become adjusted to a diet. Feeding a buffer all the time may decrease feed intake (because it is not palatable) and can increase the incidence of urinary calculi.

Levels of 1 to 3 ounces per head per day of sodium bicarbonate for cattle weighing from 500 to 1,200 pounds, respectively, are normal.

Direct-fed microbials and enzymes — Well-fed and well-managed cattle probably will not benefit from the addition of bacterial, fungal (yeast) or enzyme products to their diets. On the other hand, these additives aren’t harmful to the animal either. They are costly, though.

Cattle normally have most of the enzymes, microbes, etc., they need unless they have been starved, have had acidosis or have been treated with antibiotics or other drugs that kill or depress rumen microbes. In such instances, targeted use of some of the many highly promoted products may be effective and profitable.

Commercial show additives — There are more products promoted for show cattle than you can count. Many have catchy names and good-sounding claims. They contain everything from nutrients such as protein, fats, vitamins and minerals to enzymes, yeast, bacteria, mined earth products and unidentified stimulants. Again, well-fed and wellmanaged cattle benefit little from these costly additives.

It is wise not to use any of these products until you recognize a need. Remember that the diets formulated by top feed manufacturers are designed by professional nutritionists to be complete. Adding extra minerals, vitamins, fat, etc., can actually unbalance the diet and decrease performance! It is recommended that you first choose a good diet, feed it without any extra commercial show additives, and watch what happens. You will be surprised how many are fed this way.

If you observe problems in an individual—poor appetite, erratic appetite (first consider acidosis and management), dull hair, hoof problems, etc.— then select a product that contains what you consider to be lacking and try it. This approach will allow you to fix a problem without creating another.

Digestion and Physiology

Cattle are ruminants; their stomachs have four compartments that allow them to digest large amounts of high-fiber roughage-type feeds. This is not possible for single-stomached animals such as chickens and pigs.

The stomach compartments with the largest volumes are the rumen and reticulum; feed digesta flows from them to the omasum and abomasum (true stomach). When microbes in the rumen and reticulum ferment the feed, they break down the protein in the feed. The microbes are fed, and microbial protein and B-vitamins are synthesized. Fats are saturated, which makes them harder, while sugar, starch and fibrous carbohydrates are converted into volatile fatty acids (mostly acetic, propionic and butyric). Volatile fatty acids are absorbed into the blood and used as a source of energy by cattle.

Feed intake — Most cattle consume between 2 and 3 percent of their body weight in dry matter daily, depending on the type of ration (starter, grower or finishers). As a percentage of body weight, feed intake decreases as age, weight and condition increase.

For example, a 600-pound steer consuming 2.5 to 3 percent of its body weight would eat from 15 to 18 pounds of feed per day. A 1,200- pound steer consuming 2 to 2.5 percent can be expected to eat 24 to 30 pounds of feed per day. The effects of diet and cattle size on feed intake are noted in Table 3.

To feed each calf correctly, you must know its weight and the weight of the feedstuff. Remember: Each feed item varies in weight; a can of corn weighs slightly more than the same can filled with oats.

Starting Cattle on Grain

Starting Cattle on Grain

Feed the cattle a good-quality grass hay free-choice. Start by feeding 0.5 percent of the animal’s weight in concentrate feed. If a “starter” feed is used, it can be incrementally increased fairly rapidly to a point of full feed in 10 to 14 days. If a high-energy feed (grower) is being used, gradually increase the amount so that full feed will not be reached for 2 to 3 weeks. Do not limit hay until the cattle are safely on full feed.

Types of Diets or Rations

Most commercial feed manufacturers and show feeding programs have three major basic feed mixes: starter, grower and finisher rations (see examples in Table 3). These mixes are fed at different stages of growth and development as cattle mature physically.

The beginning ration is the starter, receiving or preconditioning mix. A starter mix is low in energy, high in roughage and fiber, and high in protein relative to the energy content. It is commonly medicated with antibiotics or coccidiostats. A high-roughage mix is bulky and fills up the rumen, preventing young calves from overeating grain while the rumen bacteria adjust from forages to grain diets.

Using a starter ration is ideal, but many feeders simply feed a limited amount of grower ration, with hay fed free-choice to get calves on feed. Either system allows for rumen bacteria to adjust and prevents acidosis. A starter ration would normally be used only for the first 2 to 4 weeks before being switched to a grower ration.

A grower mix is exactly what the name implies, a diet for cattle that are in a growing stage of 500 to 900 pounds. The mix should have at least 12 percent protein, moderate fiber and moderate energy content. The moderate energy content will properly develop the frame and muscle and help prepare the growing steer for a finishing ration. Most grower diets contain a level of roughage and energy that make the feeds suitable for a variety of uses.

Small-framed, early maturing steers can actually be finished on many grower diets. When limited to 1 to 2 percent of the animal’s live weight, grower diets are good for developing show heifers. Heifers, as opposed to finishing steers, should receive additional amounts of forage in the form of hay or pasture.

Large-framed, later maturing steers need to be moved to a finishing diet 100 to 150 days before show, or when they weigh 800 to 1,000 pounds. Some finishing diets may be too high in energy for Brahmantype cattle, and even some British and Continental cattle, especially when fed for long periods (more than 75 days).

Finishing diets can be diluted with a grower ration or hay. By blending a grower and finisher and watching your cattle’s appetite, droppings and freedom from bloat, you can develop a mix that best suits each individual animal.

A finisher ration is the last feeding stage. Finishing diets are high in energy, usually at least 50 percent corn (or related high-energy feedstuffs). Finishers should be fed carefully, particularly at the beginning. Slowly move good feeders to a full finisher ration by adding this mix to a grower diet in one-fourth portions every 7 to 14 days. Following this recommendation should enable you to change to an all-finisher ration over a 4- to 6-week period.

Later maturing cattle usually need to be on a finisher diet sooner than early maturing cattle. This will ensure they reach the correct amount of finish. Cattle finishing satisfactorily on a grower ration do not need to be switched to a full-feed finisher; most Brahman cattle should not be switched.

Some cattle feeders add steam-flaked corn to grower diets, which in effect produces a finishing ration. Realize that adding much more corn to a finisher is asking for trouble. It’s safer to use fat to increase energy intake. Breeding heifers seldom require a finisher unless it is fed on a very limited basis along with plenty of hay.

The goal is to properly finish steers at 0.35 to 0.45 inch of fat to reach their optimum yield and quality grades. Heifers need to have a moderate degree of body condition (less than that of steers). Excessive fattening of heifers at young ages diminishes future milk production potential.

A breeding heifer’s condition is referred to as a body condition score (BCS); a score of 5 for a mature heifer is similar to condition of a properly finished steer.

Diet Formulations and Examples

A series of diets shown in Table 3 illustrates nutritional relationships. Roughage in the form of cottonseed hulls (CSH) was decreased from 39 to 15 percent of the diet in diets A through G. As the CSH was reduced, corn was increased proportionally from 35 to 62 percent. Increasing corn and decreasing roughage increases the energy content (NEM, NEG or TDN) of the diets and projected gain.

Note that feed intake decreases slightly as energy content is increased. Study the relationships among feed intake, average daily gain (ADG) and feed conversion or efficiency as the size of the cattle and the diets change.

In an effort to obtain high energy and fast gain to fatten steers, you might be tempted to feed a diet similar to E. However, many cattle may suffer from acidosis from the increased level of corn, or any rapidly fermentable energy source, as listed in diet E (62 percent). Remember that acidosis is more of a problem for Brahman-type cattle, but it can affect all cattle to varying degrees.

By using 1.5 percent fat in diet F (which is basically Diet D + fat), an energy content and predicted animal performance equal to diet E is obtained without the corn level causing digestive problems. Notice that diet F has 18 percent roughage to protect against digestive problems as opposed to the 15 percent in diet E, less corn (57.5 percent versus 62 percent), but similar energy values and animal performance because of the added fat.

Fat contains 2.25 times as much energy per pound as carbohydrates (grains in a nonfermentable, nonacid producing form). Be careful when adding fat: If total fat in the diet exceeds 5 percent on a dry basis, the digestible energy value of the diet normally declines. Note that diet G contains 4.6 percent fat (5.2 percent dry basis), which is a bit too much unless 1 percent of the fat is supplied as protected fat. Protected fats are commercially available fats that have been chemically treated so that the fat does not disrupt ruminal digestion, but is digested and absorbed from the lower gut. The high level of fat in diet G is probably not needed, except for the very large framed, hard-tofinish steer. High-fat diets are not recommended for early-maturing steers or breeding heifers.

Diets A and B, with less corn and more roughage, are good for starting cattle on feed. Diets B and C work well for feeding heifers where maximum gain and fattening are not desired. Diet D would also work for heifers fed at a rate of less than 2 percent of body weight.

Management of Feed

Manure observation — Each animal differs in its capacity to consume and digest feed. The recommendations for feed intake based on percentage of body weight are simply general ranges. A better way to determine the optimal amount of feed for each steer/animal is to observe its droppings.

A consistent, firm manure patty that does not splatter when dropped to the ground indicates that the steer is on full feed with the proper amount of concentrate.

A consistent, firm manure patty that does not splatter when dropped to the ground indicates that the steer is on full feed with the proper amount of concentrate.

A watery stool (scours) usually means that the animal is taking in too much energy, and either the amount of feed or the energy level (corn) portion of the ration should be reduced. If this problem persists, severe acidosis usually results, and the steer goes off feed.

If the droppings are too firm and dry, the steer needs more feed or a higher energy concentration (more corn) in the ration. Inadequate energy intake results in lower gains and decreased finishing.

Daily hand-feeding routine Cattle should be fed twice daily, 12 hours (6 a.m., 6 p.m.) apart for best gains. If cattle need to consume more feed and are perhaps “slow eaters,” three-a-day feedings are recommended. Of course, smaller portions per feeding are advised than in the two- feeding total amounts.

Cattle that eat three times a day (6 a.m., noon and 6 p.m.) usually consume more total feed and have less digestive stress than they would if fed only twice daily. For most cattle, feeding two times a day is sufficient for optimum efficient growth and development.

Group and individual hand – feeding — Feeding cattle in groups is an excellent way to reduce labor and increase intake, especially for competitive steers. However, you must observe each steer closely, because of individual feeding varies. Some steers are dominant eaters and will consume another steer’s calculated portion, which results in some overfed and some underfed individuals. Some steers are slow eaters and, when fed together with fast eaters, uneven portions are consumed. Group feeding works best when cattle are on a full-feed growing ration.

Individual feeding requires some time and labor, but ensures that the proper amount is being consumed. You, as a feed manager, must observe the animals for results and make any necessary feeding or ration adjustments for each individual.

Bulk or Self-feeding system — This system is most appropriate for a pen of steers used for commercial steer production and not as show cattle. This labor-saving system of self-feeding corrects individual feeding variations among dominant, fast and slow eaters.

Just remember that the bulk feeder should never run out of feed. This system does not allow you to work closely with an individual animal nor does it let you control feed intake for each animal.

Feeding Commercial Steers

Commercial steers could be fed the same kinds of diets as those recommended for show steers. However, there are different goals for commercial steers than for haltered steers. The emphasis for show steers is for high weight gain and safety, with little or no emphasis on efficiency of gain. Show steer rations are more expensive than are commercial steer diets.

Commercial projects emphasize efficiency and cost of gain as well as rate of gain, with limited concern about long-toed, slightly foundered cattle (refer to the section on general health management). This means that the commercial steers should be fed low roughage, high energy diets over a shorter feeding period.

Many commercial steers are fed whole shelled corn with a commercial pelleted supplement. This method works well because whole corn is very digestible but coarse enough to have a roughage effect on the rumen; also, the commercial supplements are designed to furnish missing nutrients such as potassium.

The concept of the whole shelled corn feeding program is to self-feed the cattle. You want the cattle to eat small amounts several times a day. Cattle should nibble and chew and not gulp the feed, or efficiency could drop by 10 to 15 percent.

Start the cattle on feed with 50 percent cottonseed hulls and 50 percent corn plus the supplement. Increase the corn 5 to 10 percent every 2 to 3 days and have the animals on full feed (self-feeding) in 3 to 4 weeks.

Another approach would be to full-feed grass hay, add corn at 0.5 percent of body weight plus supplement. Increase the corn 1/2 pound per day until on full feed and then self-feed.

Once on full feed, a final diet of shelled corn, supplement and 5 percent cottonseed hulls is recommended. The hulls help hold the mix together and add a small amount of insurance against digestive problems. Corn moisture should range from 14 to 18 percent. Corn moisture at 10 to 12 percent will result in a slight increase in dry matter intake, the same gain and a slight reduction in efficiency.

The supplement should definitely contain an ionophore (preferably one that is effective against acidosis and bloat) and come as a good quality pellet in a size that will stay mixed with shelled corn. Light (400- to 500-pound) cattle should receive an all-natural protein supplement. Heavy cattle (900 pounds plus) perform well on all-urea supplements with a gradual transition of supplement types.

For the beginner — An experienced cattle feeder will obtain the greatest feed efficiency with little (5 to 10 percent) or no roughage in the final ration. However, it’s usually better for a beginning feeder to keep 5 to 10 percent roughage (cottonseed hulls mixes best) in the ration. The extra roughage reduces feed efficiency slightly, but it adds a measure of safety against serious digestive problems that can result in drastically reduced performance.

A small slab of hay during stressful weather periods or when cattle show signs of bloating or scouring can help keep them on feed and prevent serious digestive upsets.

Health Management

Maintaining good health is an important part of an overall management plan. To ensure proper performance, you must establish and maintain an effective health management program.

Disease prevention

Consult your veterinarian for advice about your health management program. It is important for cattle to be vaccinated against clostridial (blackleg) and respiratory (pneumonia) diseases. Probable vaccinations for your calf include:

Blackleg type vaccine — Clostridial vaccinations should have been completed before weaning. If not, vaccinate with 7-way at the time of purchase followed by a booster 2 to 3 weeks later and another booster 6 to 8 months later.

Tetanus vaccine — Vaccinate with a tetanus toxoid at the time of purchase. Brucellosis vaccine, for heifers only — Heifers must be vaccinated against brucellosis between 6 and 12 months old. This must be performed by a veterinarian.

Leptospirosis vaccine — Vaccinate with 3- or 5-way at purchase and give a booster every 6 months. This prevents production losses from bloody urine, loss of condition, kidney problems and decreased gains.

Metabolic Disorders

Poor nutrition and feeding management can cause health problems referred to as “metabolic disorders.” Although these are not diseases, they still can cause severe health problems. Some of the more common feed-related health problems in show cattle are acidosis, bloat, founder, scours and urinary calculi.

Acidosis — The rate of fermentation, or acid production, from a given amount of feed is just as important as the total extent of fermentation of that feed. Factors that influence fermentation rate and acid production include particle size of grains as affected by processing, meal size, rate of eating and day-to-day consistency of feed intake.

When too much acid is produced, referred to as acidosis, even for short periods, it causes a change in microbes that can then produce lactic acid. Lactic acid is a much stronger acid; when it accumulates, it causes acidosis. This acidosis causes loss of appetite, decreased rumen activity, rumen ulceration, liver abscess, founder and even sudden death.

Mild acidosis is first observed as erratic intake of feed and possibly mild bloat, followed by scouring. Loose, watery feces covered with clear gas bubbles that glisten in the light indicates acidosis.

Acidosis, sometimes referred to as “grain overload,” usually results from introducing grain too rapidly into the diet of animals coming from forage diets. The types of microbes that ferment forages are different from those that ferment grains. It normally requires 2 to 3 weeks to allow for the shift in microbial populations of the rumen and a safe transition from forage to grain diets.

Sometimes acidosis results from erratic feed consumption or simply excessive grain intake over a long period after cattle are safely on feed. A good ration should contain feeds that are not all fermented at the same rate, especially not all rapidly.

To prevent acidosis, start grain feeding slowly. Be consistent in the amount of feed fed; weigh each feeding. Make feeding changes gradually. If a feeding time is missed by more than 1 hour, skip it or feed a little hay. Do not give extra feed to make up for the missed meal. That is the worst thing you can do.

Avoid dust and fines (very small particles) and limit feeds such as molasses that are rapidly fermented. Feeding hay will provide some measure of protection. Feed one of the more effective ionophore feed additives. Because of the lost time and condition on cattle, it is important to prevent acidosis.

Treatment involves an oral administration of antacid or buffering compounds such as sodium bicarbonate, together with intravenous administration/not infusion of electrolyte solutions. This counters the acid effects and prevents further dehydration.

Getting cattle back on feed following severe acidosis is just like starting on feed initially. Give lots of hay and little concentrate.

Bloat — Bloat occurs when gas accumulates and the animal is not able to belch it out. There are many causes of bloat.

Signs of bloat are swelling high on the upper left side behind the ribs and in front of the hip bone. Cattle on full feed may show a big, full rounded middle on the left side, and even the right side to a lesser extent. A popping-out away from the general contour of the body, which looks like a basketball high on the left side, is a definite sign of serious bloat.

Many cattle may show a mild degree of bloat without any serious problems, but watch them closely, because minor bloat can advance to much more serious bloat.

To treat minor bloat, keep calves on their feet and walking, uphill if possible with head up. Drench with mineral oil.

With acute bloat, calves also can froth at the mouth, fight for breath and go down in convulsions. A severely bloated animal may die a few minutes after it falls.

As soon as you see acute bloat symptoms, call a veterinarian and administer the following treatments. Keep the animal walking, preferably uphill, with the head held up. While waiting for the veterinarian, place a stick about a foot long crossways in the calf’s mouth like a bit on a horse. This encourages chewing and tongue movements to help release gas by belching.

A large stomach tube or 1/2-inch-diameter water hose can be passed through the esophagus (be careful not to enter the trachea). This helps with ordinary bloat but is of little value in foamy or “frothy bloat.”

As the last resort (with acute bloat only), puncture the animal’s distended rumen. This should be performed by a veterinarian if at all possible. The wound is hard to heal because of infection from the rumen contents.

The best preventive measure is to avoid feeds and management practices that encourage bloat. These include too many fines and dust (sorghum is worse than corn), too much molasses, too much very high protein forage such as alfalfa or excellent grass hay and lack of any longstemmed forage in the diet.

A little dry hay that encourages cattle to salivate helps prevent bloat. Rumensin® mixed in rations is more effective in preventing minor bloat than other forms of ionophores.

Scours — Scouring (watery stool) from any cause leads to dehydration of the animal; electrolyte therapy could be needed. Causes, prevention and treatment for scours resulting from acidosis have been discussed previously.

Bloody scours may be caused by a severe case of internal parasites, bacterial infections or coccidiosis and should be treated with appropriate medication. It is important to keep pens, feeders and water troughs clean in an effort to prevent infections.

Founder — Eating too much grain, which would be expected to cause severe acidosis, frequently causes a condition known as founder. The animal’s hooves grow rapidly and there is an increased blood flow to the hooves that causes them to become tender. This cripples the animal and severely reduces feeding performance.

Urinary calculi — Kidney stones, water belly or urinary calculi can sometimes affect steers but they usually are not a problem in heifers. The condition is caused by mineral imbalances and/or diets that are too alkaline. It is common in animals on pasture or consuming feeds high in silica and in feedlot situations.

The problem is often observed in animals fed diets high in phosphorus within adequate calcium supplementation. Diets should contain 1.5 to 3.0 times as much calcium as phosphorus. Salty water seems to increase the incidence of urinary calculi. However, higher levels of salt (1 to 3 percent) in feed causes the cattle to consume more fresh water, which helps counteract the problem by increasing urine volume. Excessive and/or extended use of sodium bicarbonate can cause problems.

Ammonium chloride (1 to 1.5 ounces per head per day) in the feed acidifies urine and can be used as a preventive measure for fattening cattle in areas where problems are common. To spot a developing problem, check the hair around the urinary opening frequently for signs of mineral deposits.

Other Problems

Other problems you may encounter with your project animal include warts, ringworm, foot rot, parasites, grubs, ticks, flies, lice and coccidiosis.

Warts

Warts are caused by a virus. To treat:

✦ Keep the warts covered with oil (such as mineral oil) to starve the virus of oxygen.

✦ Recommended vaccines may work.

✦ Tie off warts with dental floss or fishing line.

✦ Cut off the warts, dice them up and place in an empty bolus (pill) to give back to the animal. This will create self-immunity. Warts also can be mixed in the animal’s feed. The warts can be taken to a veterinarian to develop a vaccine.

Ringworm

Ringworm is caused by a fungus infection of the skin. It can be spread from animal to animal or by brushes, combs or contaminated surroundings. It also can be transmitted to humans. To treat:

✦ Repeatedly apply strong tincture of iodine.

✦ Use 5 pounds of Captan® in 20 gallons of water administered by a pressure sprayer. Spray the premises, stalls and fence lines. You also can make it into a paste and spread it over the infected area.

✦ Apply bleach directly to the infected areas.

✦ Use thiabendazole mixed with dimethysulsulfoxide (DMSO) or use ivermectin.

Foot rot

Foot rot is an infection caused by bacteria that enter through a break in the skin of the hoof. It is associated with swelling between the toes that progresses to total swelling of the lower leg and causes lameness. To treat: Administer long-acting sulfa boluses (pills) and/or thoroughly cleanse the area and apply an antibacterial ointment or 5 percent copper sulfate under a bandage.

Internal parasites

Do not combine internal parasite control (deworming with a parasiticide) with grub or lice preparations. To deworm club calves, administer the first treatment upon arrival. In exactly 21 days, treat again and continue this treatment every 100 days. It is recommended to alternate types of dewormers for best results. Also, maintain care and sanitation practices in the confined areas to reduce parasite populations.

Grubs

To treat for grubs, apply pour-on treatments for show cattle at the end of May and again at the first of July (June 15 – July 15), preferably in the late afternoon to prevent blistering.

Ticks

Ticks should not be a problem in properly groomed and handled show calves.

Flies

Flies can be controlled with proper sanitation and by cleaning or removing fly breeding areas, especially manure. Also, apply fly spray with a hand sprayer on the animals and in the stalls. Fly tags, one in each ear, also seem to control flies that irritate cattle. Some owners simply tie the tags to the halter instead of placing them in the ears.

Lice

Lice are most abundant during winter and summer months. Apply insecticide in late winter and early spring months and a second application 14 days later to kill newly hatched lice. Read the label for application. For systemic parasite control, use ivermectin to control lice, flies, grubs, worms and ringworms.

Coccidiosis

Treat coccidiosis (bloody scours) with a specific cocidiostat in drench or water trough. Feed an ionophore throughout the feeding period to help prevent this condition.

Handling Calf

Animal selection, feeding and nutrition and general health maintenance are only part of a 4-H beef project. You also must handle, train and exhibit your animal. It takes proper skills, patience and practice to correctly train a calf for show.

The first month is the time when the animal will develop a trust and sense of security with its owner. It is imperative to work slowly and calmly during the early part of the training stage.

After you receive your calf, allow 7 to10 days for the calf to learn the new environment and surroundings. Then begin working with the calf. Remember: Never work alone when first breaking cattle to lead. Always have a helper in case the calf becomes unruly.

Start slowly. Try rubbing and scratching the animal while moving quietly. This should allow the calf to become familiar with your mannerisms. Begin scratching around the top (back) or tail head of the animal, not the head or face.

Halter breaking — The calf should be halter broken as early as possible to keep everyone and the calf from getting hurt. The most preferred halter to break calves is one with a padded nose band. This type of halter helps prevent serious injury and does not scratch the calf’s nose.

Place the halter on the calf and adjust it to fit correctly. For proper fit, the nose piece should be up over the nose, just under the eyes. The halter should be moderately loose. Tightness can cause sores behind the ears.

After haltering the animal, apply tension to it a couple of times before releasing. Allow the animal to drag the lead rope on the ground. As the calf walks, it will step on the lead rope and pull its head around. This should teach the calf to respond to pressure and keep the nose tender enough to make it easier to handle the first few days. The animal may be allowed to wear the halter and drag the lead rope for several days.

Always remove the halter each evening. The calf could receive blisters on the head, face and feet from rope burns if the halter remains on all day and night.

After the calf is broken to halter, do not leave the halter on unless the calf is tied or held. The calf must learn that it will be restrained whenever haltered.

Training to stand — To train a calf to stand when haltered, secure an inner tube to a post. Tie the calf to the inner tube. As the calf pulls back, the inner tube will stretch and as the calf comes forward, the inner tube will relax. The calf learns to stop the pressure on its head by stepping forward.

Never leave the calf unattended when tying the first several times! It is also a good idea to place feed, hay and water in front of the calf to reward it for doing a good job.

Training to lead — When training a calf to lead, pull on the lead rope and then give slack and allow the calf to move forward. Do not apply continuous pressure. Always pull and then release the pressure as the calf responds.

When the animal learns that the rope loosens when it walks, it will lead. Do not try to lead a calf that is not halter broken because this can encourage breakaways.

✦ Do not tie the calf behind a vehicle and pull!

✦ Do not hit the calf with any object!

✦ Do not pull on the rope with hard jerks!

✦ Do not use an electric prod or hot shot!

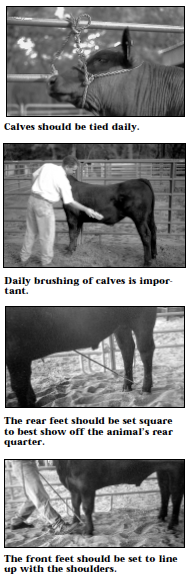

Training for the show ring — As soon as the calf starts to lead, begin daily exercise and practice proper show ring procedures. Daily exercise is important for both the condition of the animal and its response to you, the handler.

You will need a show stick to start training the calf to stand correctly. Begin by setting up the beef animal’s front feet. Push the feet back with the end of the show stick and pull them forward with the hook. After the front feet are set squarely in line with the shoulders, set the back ones in the same manner.

Slight backward or forward pressure on the halter lead also is useful in positioning feet. The feet should be set squarely under the calf. One leg should be under each corner of the body. The calf should appear natural in its stance.

After much training and practice, the calf will soon understand what is expected and will begin to set up itself. Teach the calf to stand in one place for 10 to 15 minutes to help it build stamina for the show ring.

When a calf is standing correctly, use the show stick to rub under the belly. The calf will associate standing still with getting its belly rubbed.

Daily activity — After the initial halter breaking, you should tie up your heifer or steer for a few hours each day. Every day, the animal should be rinsed off to remove dirt and encourage healthy skin and hair coat. Then, brush or blow dry the animal’s coat to condition and train the hair.

Daily activity — After the initial halter breaking, you should tie up your heifer or steer for a few hours each day. Every day, the animal should be rinsed off to remove dirt and encourage healthy skin and hair coat. Then, brush or blow dry the animal’s coat to condition and train the hair.

After this daily routine is completed, you should walk the steer to develop familiarization and confidence between yourself and the calf. When this exercise is complete, practice showing the calf with someone acting as the judge. Walk the steer in a circle to simulate a show. When the total routine is complete, feed the calf. While it is eating, you can clean and freshen the pens with bedding for use the next day. For best exercise and relaxation, the calf should be turned into a large lot for the night.

The next morning, bring the calf into the smaller lot, feeding pen, or tie it up in the shelter. Then feed it and made it comfortable in the clean, shaded shelter that has good air circulation in the summer (use fans if needed) and/or windbreak and roof in the winter for protection.

Keep the steer here until evening when you are ready to repeat the daily routine. The more you work with your calf, the more effectively it will respond to feed, training and showing while developing the healthy skin and hair coat that proper grooming encourages.

Daily management for summer months — Like people, show cattle become accustomed to daily routines. After the calf becomes comfortable with its new environment and learns the mannerisms of its owner, it is time to set up a daily routine. Summer is the time for you to seriously train and work with each calf.

Calves should be fed twice daily, exercised, cleaned, brushed and practice being shown. Clean the pen thoroughly, and keep the stalls fresh and raked, allowing each calf to be comfortable during the hot summer days.

It is best to begin feeding early in the morning before the day becomes uncomfortably warm. In Texas, a good feeding time is around 6 to 7 a.m. Feed each calf in an individual stall. While the calf is eating, you should have few problems placing the halter on the calf and tying it to a fence.

Next, prepare the stall. This includes raking, picking up manure and lightly spraying the stall with water to slightly dampen it and keep down dust. Also, make sure manure is dumped far away from the stall to keep flies and other insect populations from building up around the calf.

Next, prepare the stall. This includes raking, picking up manure and lightly spraying the stall with water to slightly dampen it and keep down dust. Also, make sure manure is dumped far away from the stall to keep flies and other insect populations from building up around the calf.

After the calf finishes eating, it is time to exercise and sharpen the showmanship skills of the calf and yourself. It takes about 15 minutes to lead, stop, set up and scratch it with a show stick.

Next, lead the calf to a wash rack and rinse it with a water hose and nozzle. After rinsing thoroughly, train the hair by brushing everything forward with a rice-root brush. The summer is not the time to grow hair, but is the time to teach and train. Even if the animal is to be shown slick shorn, it still should be kept clean. Beef cattle that are placed in a clean and sanitary environment will be more efficient performers.

After rinsing and brushing, move the calf to its clean stall. It is a good idea to keep the calf tied up until it is completely dry. This will build stamina to more effectively prepare it for show. After a couple of hours, the steer can be tied down and allowed to rest.

The calf should rest until late afternoon. At this time, the owner should clean the stall and rinse and brush the animal again if possible. End the day with the evening feeding. Again, feed as the tempera-ture begins to cool. After feeding individually, turn the calf out to exercise in a large pen. Clean the stalls and surrounding areas, and prepare for the next day.

Preparing for Show

Many people work with calves all year and then take them to the show to find out the calves are in the wrong weight class, will not eat, will not drink and will not show. Proper conditioning of show cattle can make the difference between a champion and just another calf at a show. Every calf is a different individual and must be programmed to demonstrate its strong traits.

The importance of the condition of a show steer can be compared to that of a superior athlete who becomes an Olympic champion. Show cattle must be trained and fed with a definite purpose in mind in order to obtain a championship banner.

Here are some more tips for developing future champions in the show ring:

✦ Cattle are creatures of habit and have good memories. Develop a routine and follow it each day. A daily routine makes chores much easier. For example, exercise the calf, show it by setting it up and make it stand properly; then brush and feed it last.

✦ Weigh the calf periodically to monitor its gain. Decide which weight class you will show your calf in, and shoot for that weight. Class breakdowns from previous shows are very helpful in determining desired weights.

✦ To be a good showman, you need a well-trained calf. Teach the calf to stop and lead with its head up. A good daily practice is to pull the animal’s head up to a stop so both front feet are placed squarely under the front end. Using a show stick with a blunt point on the end, teach the calf the use of a show stick by stroking its underside while it is tied. Stroke the animal, then place the foot in the correct place. After the calf moves its feet properly when tied, it is ready to be led and have its feet placed while you hold its halter lead. Teach the calf to keep its top level and to lead and walk freely. Work often for several minutes at a time, rather than a few long, drawn-out periods.

✦ When training a calf or working and brushing hair, tie the calf to a high rail rather than placing it in a blocking chute. Working cattle in this manner tends to make them easier to handle and makes them more accustomed to strange movements at the show. Before washing the calf, remove dirt and manure from the hair with a comb or brush.

✦ Two weeks before the first show of the season, start handling the calves just as you will at the show. A good practice is to make some type of “tie outs” at home along a fence and tie the calves as you will at the show. The bedding should be the same type you will use at the show. Calves should be tied in the barn all day and exercised each afternoon. Another method is to tie the calves during the day and turn them loose in the lot or small trap at night. Feed and water the calves just as you would at the show—twice a day out of the same feed and water buckets you will use at the show. Some handlers add small amounts of molasses to the water to get the steers accustomed to drinking sweet water. The molasses will hide the taste of chlorine in city water.

Not everyone can have the best, most complete beef project. However, you can gain an advantage in the show ring if you work at home correctly. You have selected the best possible animal, you have studied its nutritional needs and fed it properly, and you have maintained its general health. You also have worked tirelessly in handling and training your animal. Remember to practice your showmanship skills, because practice makes perfect. A great showperson always leaves a favorable impression on the judge.

Management Calendar

April

✦ Buy a show prospect.

✦ Place on starter ration.

✦ Administer health shots.

✦ Administer a parasiticide to control internal parasites.

May

✦ Halter break and begin training.

✦ Trim hooves.

✦ Treat for external flies (stable, horn, face flies).

June

✦ Begin training. The summer is the time for you and the animal to gain trust in one another.

✦ State steer validation for entry to major shows.

Each county will set their own individual date sometime within the month.

✦ Move to grower diet.

✦ Administer a parasiticide.

✦ Treat for external flies (stable, horn, face flies).

July

✦ Trim hooves.

✦ Consult the county Extension agent to find local prospect shows and participate in a

few local shows for practice.

✦ Treat for external flies (stable, horn, face flies).

August

✦ Treat for external flies (stable, horn, face flies).

✦ Administer a parasiticide.

September

✦ Treat for external flies (stable, horn, face flies).

✦ Trim hooves (if needed).

✦ Implant if needed.

✦ Trim hooves.

✦ Move to finisher ration.

October

✦ Administer a parasiticide.

November

✦ Trim hooves.

✦ Implant if needed.

December

✦ Administer a parasiticide.

✦ The deadline for major shows is before December 1.

Check with the county Extension office for the deadline in each county.

January

✦ Trim hooves (if needed).

✦ Show.

Knowledge and Skills

Texas 4-H – Managing Beef Cattle For Show—Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills

Instructors who use this curriculum will address the following TEKS components as outlined by the

Texas Education Agency.

Social Development

The student understands the basic components such as strategies, protocol, and rules of individual activities.

Business Education

The student implements components of productivity. The student demonstrates an understanding of personal financial management.

English and Language Arts

Communication Applications — The student is able to explain the importance of effective communication skills in professional and social contexts.

Speech Communication — The student is able to recognize and explain the importance of communication in social, academic, citizenship and professional roles.

Agricultural Science and Technology Education

Introduction to World Agricultural Science and Technology — To be prepared for a career in the broad field of agriculture/agribusiness, the student attains academic skills and knowledge, and acquires knowledge and skills related to agriculture/agribusiness.

Plant and Animal Production — The student knows the importance of animals and their influence on society.

Agribusiness Management and Marketing — The student defines and examines agribusiness management and marketing and its importance to the local and international economy; the student defines the importance of records and budgeting in agribusiness.

Personal Skill Development in Agriculture — The student demonstrates personal skills development related to effective leadership; the student communicates effectively with groups and individuals; the student demonstrates the factors of group and individual efficiency.

Animal Science — The student explains animal anatomy and physiology related to nutrition, reproduction, health and management of domesticated animals; the student determines nutritional requirements of ruminant and nonruminant animals; the student explains animal genetics and reproduction; the student recognizes livestock management techniques.

Advanced Animal Science — The student demonstrates principles relating to the interrelated human, scientific and technological dimensions of scientific animal agriculture and the resources necessary for producing domesticated animals; the student examines animal anatomy.

Developmental Assets and Life Skills

Youths that have learning experiences through this curriculum may develop the following assets and life skills which contribute to their personal development.

Developmental Asset Search Institute

Support

#1 Family Support

#3 Other adult relationships

Positive Values

#30 Responsibility

Social Competence

#32 Planning and Decision Making

Positive Identity

#37 Personal Power

#39 Sense of Purpose

#40 Positive View of Personal Future

Targeting Life Skills Model Iowa State University Extension

Nurturing Relationships

Self Responsibility and Self-esteem

Social Competence

Goal Setting and Personal Feeling