Download PDF | Email for Questions

Forage Intake | Sources of Supplemental Protein | Feeding Energy | Supplementation Strategies

Supplementing nutrients to cattle—as concentrated feeds, harvested forages, or a complementary grazing program— accounts for a signi cant portion of annual production costs in a cattle operation. To optimize productivity of today’s cattle operations, some supplemental nutrients will be required at critical periods during the annual production cycle. However, producers need to avoid unnecessarily compounding this cost by feeding too much, too little, or using range and pasture forages ine ciently. A producer should provide supplemental nutrients with minimal feed inputs. A primary objective is to use forage e ciently.

The Current Situation

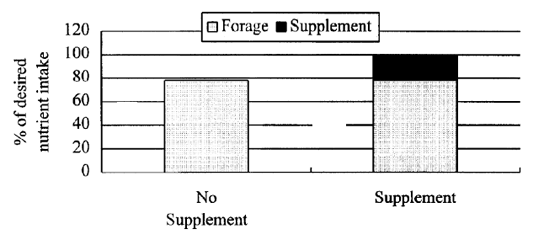

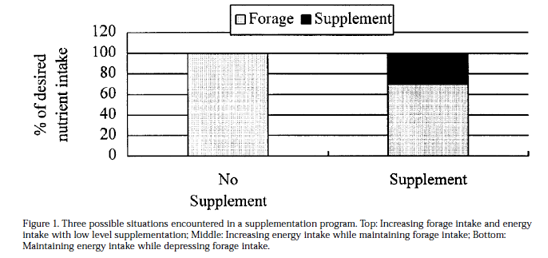

An important aspect of selecting a supplement is knowing how it a ects daily forage intake. In many situations, the success or failure of a supplemental feeding program hinges on this factor. Three common situations (Figure 1) include:

Situation 1

Cattle performance fails to meet production goals. Perhaps cows are not regaining condition as needed, or stocker calves and replacement heifers are gaining weight too slowly. Forage availability is not limiting intake, but its quality (in many instances, its protein content) is limiting intake, and possibly forage digestion. As a result, daily energy and protein intake are below daily requirements. To improve cattle performance, select a supplement that will stimulate forage intake and digestion (see top chart in Figure 1).

Situation 2

Again, cattle performance falls short of production goals. Forage availability may or may not be limiting forage intake. Instead, production goals are simply higher than can be achieved from the forage resource. First, consider a supplement that will sustain forage intake and digestion at the present level (to assure e cient forage utilization) but provide the additional nutrients required to increase performance (see middle chart in Figure 1). If this approach does not improve performance as needed, it may be necessary to feed more supplement and sacri ce some efficiency of forage utilization.

Situation 3

In this situation, forage and energy intake are currently suf- cient to meet production goals. However, due to climate or management needs, future forage supplies will be limited. A precipitation shortage may limit forage supply for fall and winter. Or, because of purchasing opportunities, large numbers of stocker cattle may be bought in late summer and fall before the rapid spring growth period for cool-season annual forages. Both can result in higher forage requirements than forage supply. A supplemental feeding program to reduce forage intake but maintain total energy intake may be desirable (see bottom chart in Figure 1).

The key to success in these three situations is to stimulate maintain, or reduce forage intake. The supplemental feeding strategy required for each is different.

Forage Intake

Forage Intake and Diet Crude Protein Ruminal Requirements

Microbial fermentation in the rumen supplies most of the energy and protein metabolized by cattle. As in the host animal, microbes in the rumen require a balanced supply of energy and nitrogen to function efficiently. The National Research Council (1984) proposed that ruminal microbes can synthesize about 113 grams of bacterial crude protein from 1 kilogram of Total Digestible Nutrients (TDN) (0.11 pound of bacterial crude protein per 1 pound of TDN). An imbalance of nitrogen and energy in the rumen can result in reduced microbial protein production, reduced forage digestion, and an unrecoverable loss of nutrients. Coupled with an unbalanced supply of metabolizable nutrients for the animal tissues, these changes can lower forage intake and cattle performance. Providing a balanced, or in some instances, unbalanced, supply of nutrients to the rumen is a key to obtaining the desired intake and production response.

Forage Intake

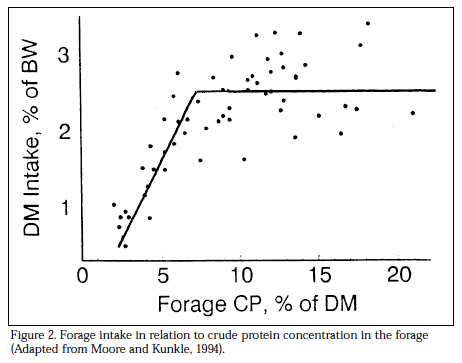

Daily energy intake is the primary factor limiting cattle performance on forage diets. In many instances with warm-season perennial forages and possibly cool-season perennial forages at advanced stages of maturity, an inadequate supply of crude protein in the forage further limits energy intake. An example of the relationship between crude protein content of forages and forage intake is presented in Figure 2 (adapted from Moore and Kunkle, 1994). Intake declines rapidly as forage crude protein falls below about 7 to 8 percent, a relationship attributed to a deficiency of protein in the rumen.

If a forage contains less than 7 to 8 percent crude protein, feeding a protein supplement will improve energy and protein status of cattle by improving forage digestibility and forage intake. For example, in Figure 1, at a crude protein content of 5 percent, forage intake is about 1.6 percent of body weight, while at 7 to 8 percent crude protein, forage intake is 2.3 percent of body weight, or 44 percent higher. Kansas State University researchers recently concluded that various protein supplements increased forage intake on average 36 percent. When high protein

(greater than 30 percent crude protein) supplements were used, response varied from about 30 to 60 percent.

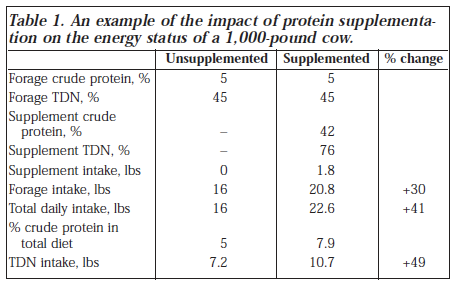

Improved forage intake boosts energy intake and demonstrates why correcting a protein deficiency is usually the first supplementation priority. For example, in Table 1, the estimated impact of protein supplementation on energy status is shown. Forage intake was increased 30 percent in response to a modest amount (0.18 percent of body weight) of protein supplement, resulting in a 49 percent increase in TDN intake by the cow.

Crude protein content of some forages must drop to about 5 percent before intake declines. Intake of some forages declines when crude protein is as high as 10 percent. Part of the variation can be attributed to differences in nutrient requirements of the cattle used in the research, with the remainder attributed to inherent differences among forages, which present differing proportions of nutrients to rumen microbes. Response of intake to a single nutrient such as crude protein would not be expected to be similar among all forages.

Ruminal microbes need a balanced supply of energy and protein. Figure 2 shows how to evaluate the balance of energy and protein in forages. In this case, the percentage digestible organic matter (DOM; representing available energy) is ratioed against the percentage crude protein (CP). Theoretically, ruminal microbes require a ratio around 4:1. As the DOM: CP ratio becomes larger, the amount of energy available to microbes exceeds the amount of available protein and limits microbial activity. Forage intake is negatively related to the DOM:CP ratio. Some researchers now suggest a ratio of 6:1 to 8:1 as a threshold value. If a forage has a higher ratio, supplemental protein may be needed. If the ratio is lower, the rumen is in balance or may require additional energy.

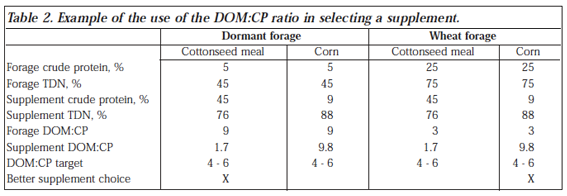

In Table 2 the dormant forage has a TDN content of 45 percent and crude protein content of 5 percent, a DOM:CP ratio of 9:1. To increase forage intake, the supplement should shift the ratio toward 6:1. Use a supplement with a relatively low DOM:CP ratio. Cottonseed meal or another protein concentrate is the better supplement option.

If the objective is to sustain or possibly reduce forage intake, the supplement should maintain the current ratio or shift the ratio higher. This supplement should have a relatively high DOM:CP ratio. If corn is selected, the DOM:CP ratio of the total diet is virtually unchanged, and ruminal nutrient balance will not be improved.

In contrast, the wheat forage in Table 2 has a relatively low DOM:CP ratio, indicating that available protein in the rumen may be exceeding the energy supply. Therefore, a small amount of feed with a high DOM:CP ratio will shift the diet toward the optimum.

Both scenarios are supported by research and field observations with grazing cattle. In northeast Texas, steers grazing rye/ryegrass were fed 1 to 2 pounds/day of a corn supplement. The cattle had a supplement conversion efficiency of 1 to 3 pounds of supplement per pound of added gain. Cattle grazing warm-season perennial grasses with DOM:CP ratios greater than 6:1 generally convert a concentrated natural protein supplement with an efficiency of 1.5 to 3 pounds of supplement per pound of added gain. The conversion efficiency of low-protein energy supplements on warm season perennials ranges from 6 to more than 10 pounds of supplement per pound of added gain.

Sources of Supplemental Protein

Supplemental protein is available in many forms. Feedstuffs and formulated feeds containing less than 10 percent crude protein to more than 60 percent crude protein are available. To complicate things further, crude protein may be from a natural protein source, a nonprotein nitrogen source, or a mixture of the two. An additional consideration may be the ratio of ruminally degradable protein and escape or bypass protein.

Crude protein concentration

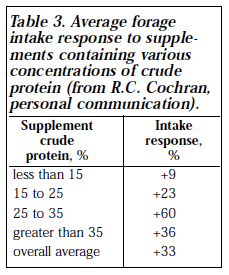

In a review from Kansas State, supplements were categorized by crude protein content to compare intake responses (Table 3). If the objective is to optimize forage intake and use, it is easy to see that the supplement should contain more than 25 percent crude protein. These are average responses so the minimal protein content should probably be in excess of 30 percent. Intake response appeared to decline with supplements containing more than 35 percent crude protein. The decline was attributed to high levels of nonprotein nitrogen and escape protein in some of the experimental supplements.

Escape or Ruminally Degradable Protein

Escape protein refers to protein not degraded in the rumen that escapes into the small intestine and is then degraded. Protein concentrates of plant origin, such as cottonseed meal and soybean meal, contain ruminally degradable protein and escape protein. In situations where the objective is to stimulate or sustain forage intake, ruminally degradable protein is the first priority because of the need to provide the rumen microbes with nitrogen. Feeding a protein source with high escape potential may not stimulate ruminal activity, and forage intake and performance response will be lower. Research results favor using ruminally degradable protein sources over escape protein sources for cattle consuming forages of low protein content. According to guidelines, 60 to 70 percent of the supplemental protein should be ruminally degradable protein, and the total diet should contain 0.1 to 0.12 pounds of ruminally degradable protein per pound of digestible organic matter.

If supplying ruminally degradable protein does not improve production (see situation 2), then supplemental escape protein may be useful. The most consistent responses have been observed in cattle grazing cool-season annual (rye/ryegrass) and perennial (orchardgrass, bromegrass) forages, especially those with 12 to 20 percent crude protein that is highly degradable in the rumen. The high degradability of the forage protein results in nitrogen being absorbed from the rumen without being converted to microbial protein. This nitrogen cannot be completely used by the animal. Therefore, supplemental protein must be supplied as escape protein. In some instances with high quality forages, both forage intake and weight gain increased when cattle were fed supplemental escape protein. This is an inconsistent response, and feeding a small quantity of an energy supplement (corn) may give the same performance response. The two supplements may accomplish the same end—supplying protein directly to the small intestine or stimulating ruminal protein synthesis.

Recent research indicates that escape protein may play a role in reproduction. Supplemental escape protein may affect postpartum interval and fertility of lactating cows by altering metabolism and endocrine function

Nonprotein nitrogen sources

Ruminal microbes can convert nonprotein nitrogen (NPN) into microbial protein. If ruminal microbes need a source of nitrogen to stimulate digestion and intake, it would seem that NPN would be useful. Unfortunately, research does not support this concept. For reasons yet to be identified, supplements containing NPN from urea and biuret are not used as efficiently as natural protein supplements. Studies have shown that the crude protein equivalent from urea and biuret is used at an efficiency of 0 to 50 percent when supplemented to cattle on low- to moderate-quality forages. Research is under way to refine recommendations for using NPN in supplements for grazing cattle. Some feed ingredients such as corn steep liquor contain significant quantities of NPN but are used quite well by grazing cattle.

Forage availability

Forage intake does not respond to protein supplementation if forage availability is limiting. The highly efficient response to protein supplements is due in large part to the higher forage intake.

Feeding Energy

If performance is limited by energy intake, why not directly increase energy intake with an energy supplement (low protein, high energy) rather than a more expensive protein supplement (high protein, moderate to high energy)? Because of the potential impact on forage intake and ultimately the energy status of the cattle. The varied responses to energy supplements make it difficult to predict the outcome of feeding energy supplements.

Substitution

A common frustration with feeding energy sources is the substitution effect. Substitution occurs when the supplemental feed substitutes for forage by reducing forage intake. As a result, the energy intake of the animal is not increased to the desired level because forage energy intake is reduced. As a general rule, 1 pound of an energy-dense feed reduces forage intake by 0.5 to 1 pound. The substitution rate depends on forage quality, level of protein in the supplement, energy source, and feeding rate. The substitution rate increases as forage quality increases; the rate decreases as the level of protein in the supplement increases; and the rate tends to increase as supplement intake increases.

Feeding hay also results in substitution. As the amount of hay fed daily increases, forage intake from the pasture source will decrease because of fill from the hay replacing fill from the pasture.

Feeding rate and frequency

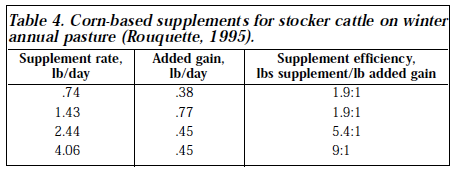

Feeding low-protein, energydense supplements at rates of less than 0.3 percent of body weight per day probably has little impact on forage intake and may sometimes increase intake. As the feeding rate is pushed higher, forage intake will begin to decline due to substitution and performance will not increase as rapidly as expected (Table 4). In this study, calves grazing winter annuals were fed varied levels of a corn-based supplement. Except for the second feeding level, the supplement increased weight gain to the same degree regardless of the amount fed daily. The efficiency of supplementation declined at higher feeding rates, indicating that the supplement was probably reducing forage intake by the calves. Feeding frequency (for instance, daily vs. alternate days) may also affect animal response. Feeding smaller amounts more frequently decreases the probability of negative impacts on forage intake. Feeding larger quantities less frequently increases the likelihood of negative impacts on forage utilization (as well as the potential for bloat and acidosis).

Energy source

To sustain or possibly improve the current level of forage intake but increase the total daily energy intake, a supplement with a moderate level of protein will be required to assure adequate ruminal protein supply. Limit the quantity of starchy feed ingredients (corn, milo, wheat), and use alternative digestible fiber energy sources (soybean hulls, wheat middlings, corn gluten feed) as primary energy sources. Using these feed ingredients will not totally eliminate the possibility of substitution.

The crude protein level in these supplements is a key consideration in terms of obtaining the desired outcome. Feeding rates should be about 0.3 to 0.5 percent of body weight.

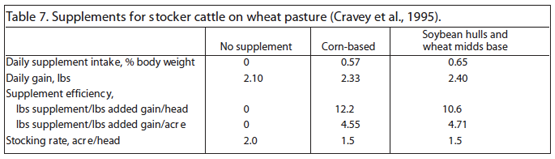

Producers who want to reduce forage intake should feed high rates of energy supplements (especially starchy feeds). For instance, Oklahoma research (Cravey et al., 1994) demonstrated that feeding 0.7 to 1 percent of body weight per day of a corn-based supplement resulted in a 1:1 substitution rate. However, stocking rate could be increased 33 percent without sacrificing steer gains (Table 7). This same approach may be useful in situations where stocking densities are too high during the dormant period or under drought conditions.

Supplementation Strategies

Strategies for Situation 1 (Table 1):

Problem: Performance is lower than desired to meet production objectives

Forage availability: Adequate and not limiting forage intake Forage quality: Crude protein is low

Forage consumption: Lower than potential forage intake because of the low crude protein concentration

Objective: Improve performance by increasing utilization of standing forage

Strategy: Feed a small amount of supplement to stimulate intake and digestion

Supplement type: High protein content (greater than 30 percent)

Preferably all natural protein but some NPN is acceptable in limited amounts with certain classes of cattle Minimum of 50 to 60 percent ruminally degradable protein

Feeding rate: 0.1 to 0.3 percent of body weight per day

Feeding frequency: Daily, or 2 or 3 days weekly (prorate 1 week of feed into 2 or 3 feedings)

Efficiency: 1.5 to 3 pounds supplement per pound of added weight gain in growing cattle and mature cows in mid-to-late gestation on late summer forage.

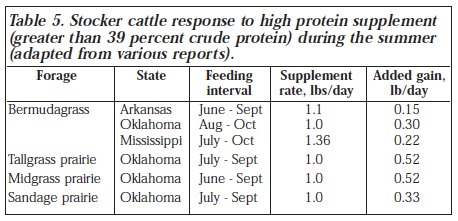

Results from this approach are shown in Table 5. High protein supplements were fed in relatively small amounts to increase weight gain efficiently by stocker calves. Responses appeared to be better on rangeland than on bermudagrass, probably reflecting differences in the DOM:CP ratio of the forages.

Strategies for Situation 2:

Problem: Performance is lower than desired to meet production objectives

Forage availability: May or may not be limiting forage intake

Forage quality: May or may not be limiting forage intake

Forage consumption: May or may not be limited

Total nutrient consumption: Lower than required to meet production goals

Objective: Improve performance by supplying additional nutrients without reducing the intake and utilization of standing forage

Strategy: Feed a supplement to sustain (and possibly stimulate) forage intake but increase total energy intake

Supplement type: 20 to 30 percent crude protein

Preferably all natural protein, some NPN may be acceptable in limited amounts

Minimum of 50 to 60 percent ruminally degradable protein; however, in some cases, the protein concentration as well as the percentage escape protein may be increased to increase total protein supply Preferably use digestible fiber feeds as the primary energy substrate

Some starchy feeds at low levels are acceptable

Feeding rate: 0.3 to 0.5 percent of body weight per day

Feeding frequency: Daily or minimum 3 days weekly (prorate 1 week of feed into 3 feedings)

Efficiency: Usually 5 to 10 pounds of supplement per pound of added weight gain in growing cattle and mature cows in mid-to-late gestation

Results in Table 6 provide a good example of this strategy. Lightweight calves were grazing rangeland. Soybean meal alone provided needed protein and improved weight gains. After correcting the pr otein de cien – cy, performance was enhanced by adding wheat middlings to the soybean meal and feeding at a higher rate.

Strategies for Situation 3:

Problem: Performance is currently meeting production objectives, but forage availability is anticipated to limit performance in the future

Forage availability: Currently adequate and not limiting intake but will be limited in the future

Forage quality: May be high or low

Forage consumption: Currently adequate but will be limited in the future

Objective: Maintain current level of perf ormance but extend forage supply into the future.

Strategy: Feed a supplement that will depr ess forage intake but maintain total energy intak e Supplement type 1:0 to 18 percent crude protein

Grain and grain byproducts

Feeding rate: 0.7 to 1.0 percent of body weight per day (possibly higher)

Feeding frequency: Daily

Efficiency: Usually in excess of 10 pounds of supplement per pound of added weight gain in growing cattle

Allows f or higher stocking densities which improves efficiency per acre rather than per head

Efficiency per acre will range from 5 to 10 pounds of added gain per acre per pound of supplement fed

Feeding steers supplement at about 0.60 percent of body weight not only improved daily gains but also reduced the land area required by a steer during winter wheat grazing (Table 7). Supplement efficiency exceeded 10 pounds supplement per pound of added weight on an individual animal basis.

However, the high feeding level reduced the steers’ forage intake and allowed for a higher stocking rate (head/acre). When expressed per acre of grazing land, the supplement efficiency was less than 5:1.

To control costs and optimize performance, evaluate each situation and develop a set of objectives for the feeding program.