Dennis B. Herd and L.R. Sprott

Download the PDF | Email for Questions

Practical Importance | Body Condition Scores | Guidelines for BCS | Effect on Reproduction | Critical BCS | Supplementation | Nutritional Management

The percentage of body fat in beef cows at specific stages of their production cycle is an important determinant of their reproductive performance and overall productivity. The amount and type of winter supplementation required for satisfactory performance is greatly influenced by the initial body reserves, both protein and fat, of the cattle at the beginning of the wintering period.

Profitability in the cow-calf business is influenced by the percentage of cows in the herd which consistently calve every 12 months. Cows which fail to calve or take longer than 12 months to produce and wean a calf increase the cost per pound of calf produced by the herd. Reasons for cows failing to calve on a 12-month schedule include disease, harsh weather and low fertility in herd sires. Most reproductive failures in the beef female can be attributed to improper nutrition and thin body condition. Without adequate body fat, cows will not breed at an acceptable rate. The general adequacy of diets can be determined by a regular assessment of body condition.

To date, there has been no standard system of describing the body condition of beef cows which could be used as a tool in cattle management and for communication among cattlemen, research workers, Extension and industry advisors. This publication’s purpose is to outline a system for evaluating beef cow’s body reserves and to relate the evaluation to reproductive and nutritional management. When used on a regular and consistent basis, body condition scores provide information on which improved management and feeding decisions can be made.

Practical Importance of Body Condition Scoring

Variation in the condition of beef cows has a number of practical implications. The condition of cows at calving is associated with length of post partum interval, subsequent lactation performance, health and vigor of the newborn calf and the incidence of calving difficulties in extremely fat heifers. Condition is often overrated as a cause of dystocia in older cows. The condition of cows at breeding affects their reproductive performance in terms of services for conception, calving interval and the percentage of open cows.

Body condition affects the amount and type of winter feed supplements that will be needed. Fat cows usually need only small amounts of high protein (30 to 45 percent) supplements, plus mineral and vitamin supplementation. Thin cows usually need large amounts of supplements high in energy (+70 percent TDN), medium in protein (15 to 30 percent), plus mineral and vitamin supplementation. Body condition or changes in body condition, rather than live weight or shifts in weight, are a more reliable guide for evaluating the nutritional status of a cow. Live weight is sometimes mistakenly used as an indication of body condition and fat reserves, but gut fill and the products of pregnancy prevent weight from being an accurate indicator of condition. Live weight does not accurately reflect changes in nutritional status. In winter feeding studies where live weight and body condition scores have been measured, body condition commonly decreases proportionally more than live weight, implying a greater loss of energy relative to weight.

Body condition affects the amount and type of winter feed supplements that will be needed. Fat cows usually need only small amounts of high protein (30 to 45 percent) supplements, plus mineral and vitamin supplementation. Thin cows usually need large amounts of supplements high in energy (+70 percent TDN), medium in protein (15 to 30 percent), plus mineral and vitamin supplementation. Body condition or changes in body condition, rather than live weight or shifts in weight, are a more reliable guide for evaluating the nutritional status of a cow. Live weight is sometimes mistakenly used as an indication of body condition and fat reserves, but gut fill and the products of pregnancy prevent weight from being an accurate indicator of condition. Live weight does not accurately reflect changes in nutritional status. In winter feeding studies where live weight and body condition scores have been measured, body condition commonly decreases proportionally more than live weight, implying a greater loss of energy relative to weight.

Two animals can have markedly different live weights and have similar body condition scores. Conversely, animals of similar live weight may differ in condition score. As an example, an 1,100 pound cow may be a 1,000 pound animal carrying an extra 100 pounds of body reserves, or a 1,200 pound cow which has lost 100 pounds of reserves. These two animals would differ markedly in both biological and economical response to the same feeding and management regime with possible serious consequences.

The body composition of thin, average and fat cows is illustrated in Table 1. Protein and water exist in the body in a rather fixed relationship. As the percentage of fat in the body increases, the percentage of protein and water will decrease. The gain or loss of body condition involves changes in protein and water as well as fat, though fat is the major component. Breed, initial body condition, rate of condition change and season affect the composition and energy value of weight gains or losses. Body condition scoring provides a measure of an animal’s nutrition reserves which is more useful and reliable than live weight alone.

In commercial practice, body condition scoring can be carried out regularly and satisfactorily in circumstances where weighing may be impractical. The technique is easy to learn and is useful when practiced by the same person in the same herd over several years.

Body Condition Scores

Body condition scores (BCS) are numbers used to suggest the relative fatness or body composition of the cow. Most published reports are using a range of 1 to 9, with a score of 1 representing very thin body condition and 9 extreme fatness. There has not been total coordination by various workers concerning the descriptive traits or measures associated with a BCS of 5. As a result, scoring done by different people will not agree exactly; however, scoring is not likely to vary by more than one score between trained evaluations, if a 1 to 9 system is used. For BCS to be most helpful, producers need to calibrate the 1 to 9 BCS system under their own conditions.

Guidelines for BCS

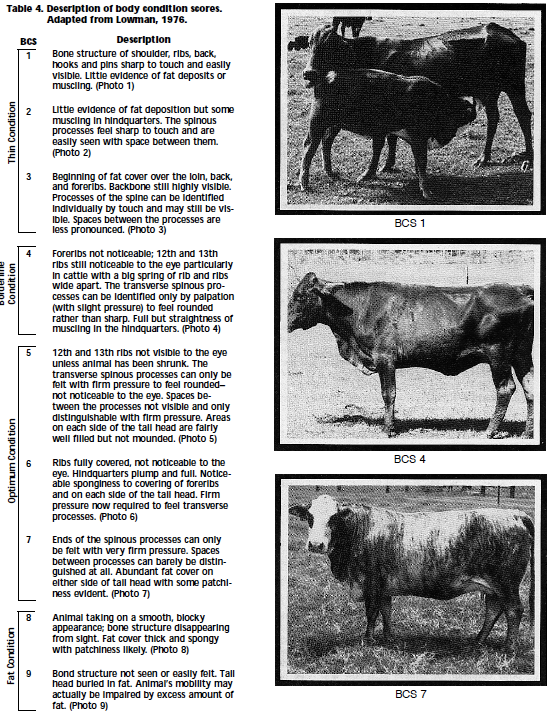

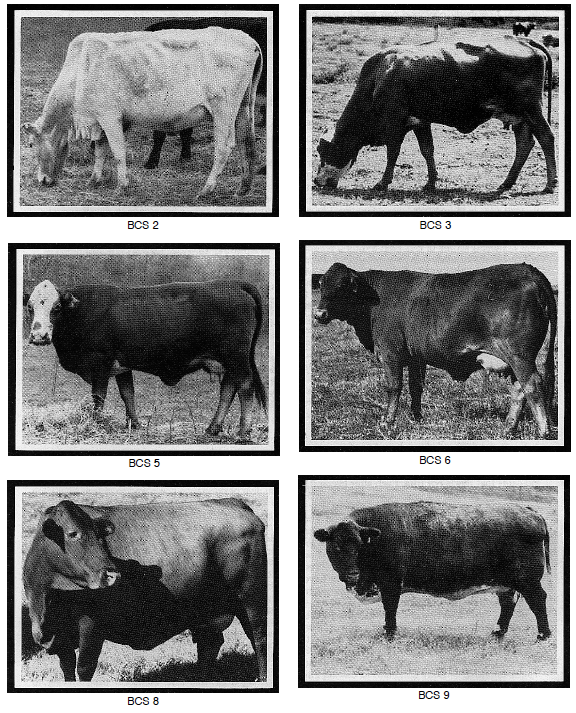

Keep the program simple. A thin cow looks very sharp, angular and skinny while a fat one looks smooth and boxy with bone structure hidden from sight or feel. All others fall somewhere in between. A description of conditions scores is given in Table 4.

A cow with a 5 BCS should look average—neither thin nor fat. In terms of objective measures, such as fat cover over the rib, percent body fat, etc., a BCS 5 cow will not be in the middle of the range of possible values but rather on the thin side. A BCS 5 cow will have 0.15 to 0.24 inches of fat cover over the 13th rib, approximately 14 to 18 percent total empty body fat and about 21 pounds of weight per inch of height. (See Table 2 for the range in values for all condition scores.) The weight to height ratio has not been as accurate as subjective scoring for estimating body composition. Pregnancy, rumen fill and age of the cow influence the ratio and reduce its predictive potential. The ratio of weight to height can help separate the middle scores from the extremes.

A cow with a 5 BCS should look average—neither thin nor fat. In terms of objective measures, such as fat cover over the rib, percent body fat, etc., a BCS 5 cow will not be in the middle of the range of possible values but rather on the thin side. A BCS 5 cow will have 0.15 to 0.24 inches of fat cover over the 13th rib, approximately 14 to 18 percent total empty body fat and about 21 pounds of weight per inch of height. (See Table 2 for the range in values for all condition scores.) The weight to height ratio has not been as accurate as subjective scoring for estimating body composition. Pregnancy, rumen fill and age of the cow influence the ratio and reduce its predictive potential. The ratio of weight to height can help separate the middle scores from the extremes.

There is controversy about whether one needs to feel the cattle to determine fatness (Figure 1) or simply look at them to assess condition scores. A recent  study indicated that cattle could be separated equally well by palpation of fat cover or by visual appraisal, but the set point or average score may vary slightly depending on the method used. For cattle with long hair, handling is of value, but when hair is short, handling is probably not necessary. Keep in mind that shrink can alter the looks and feel of the cattle as much as one score. Animals in late pregnancy also tend to look fuller and a bit fatter. By recognizing differences in body conditions, one can plan a supplemental feeding program so that cows are maintained in satisfactory condition conducive to optimum performance at calving and breeding. These scores are meant to describe the body condition or fatness of a cow and have no implications as to quality or merit. Any cow could vary in condition over the nine-point system, depending on health, lactational status and feed supply.

study indicated that cattle could be separated equally well by palpation of fat cover or by visual appraisal, but the set point or average score may vary slightly depending on the method used. For cattle with long hair, handling is of value, but when hair is short, handling is probably not necessary. Keep in mind that shrink can alter the looks and feel of the cattle as much as one score. Animals in late pregnancy also tend to look fuller and a bit fatter. By recognizing differences in body conditions, one can plan a supplemental feeding program so that cows are maintained in satisfactory condition conducive to optimum performance at calving and breeding. These scores are meant to describe the body condition or fatness of a cow and have no implications as to quality or merit. Any cow could vary in condition over the nine-point system, depending on health, lactational status and feed supply.

Effect on Reproductive Performance Calving Interval and Profitability

Calving interval is defined as the period from the birth of one calf to the next. To have a 12-month calving interval, a cow must rebreed within 80 days after the birth of her calf. Cows that do, produce a pound of weaned calf cheaper than cows that take longer than 80 days to rebreed.

In a Hardin County, Texas study, maintenance costs were compared for cows with a 12-month calving interval against those with a longer interval. Costs of production per calf from cows with intervals exceeding 12 months ranged from $19 to $133 more than for calves from cows with 12-month intervals. To compensate for increased production costs, calves from cows with extended calving intervals must have a heavier weaning weight than calves from cows with intervals of 12 months or less. Otherwise, an increase in sale price must occur. Depending on either factor for compensation is an unreasonable gamble.

The results of 5 trials which explain the effect of body condition at calving on subsequent reproductive performance are shown in Table 3. In trial 1 the percent of cows that had been in heat within 80 days after calving was lower for cows with a body condition of less than 5 than for cows scoring more than 5. Low body condition can lead to low pregnancy rates as evidenced in the other four trials. In all instances, cows scoring less than 5 at calving time had the lowest pregnancy rates indicating that thin condition at calving time is undesirable. The acceptable body condition score prior to calving is at least 5 or possibly 6. These should be the target condition scores at calving for all cows in the herd. Anything higher than 6 may or may not be helpful. Scores at calving of less than 5 will impede reproduction.

BCS at Breeding

Cows should be in good condition at calving and should maintain good body condition during the breeding period. Table 5 shows results of a trial involving more than 1,000 cows where the effect of

body condition during the breeding season on

pregnancy rates was studied. That trial supports the fact that condition scores of less than 5 during breeding will result in extremely low pregnancy rates. Proper nutrition during the breeding season is necessary for acceptable reproduction.

Long Breeding Seasons Not the Answer

Some producers believe long breeding seasons are necessary to achieve good reproductive performance. Evidence in Table 3—Trial 4 and Table 5 indicates that this is not true. Even after five and six months of breeding, the cows scoring less than 5 at calving and during breeding did not conceive at an acceptable level. Until they have regained some body condition or have had their calf weaned, most thin cows will not rebreed regardless of how long they are exposed to the bulls. Trials have shown that thin cows may take up to 200 days to rebreed. Cows requiring that long to rebreed will not have a 12- month calving interval, which subsequently reduces total herd production.

Some producers believe long breeding seasons are necessary to achieve good reproductive performance. Evidence in Table 3—Trial 4 and Table 5 indicates that this is not true. Even after five and six months of breeding, the cows scoring less than 5 at calving and during breeding did not conceive at an acceptable level. Until they have regained some body condition or have had their calf weaned, most thin cows will not rebreed regardless of how long they are exposed to the bulls. Trials have shown that thin cows may take up to 200 days to rebreed. Cows requiring that long to rebreed will not have a 12- month calving interval, which subsequently reduces total herd production.

Calving intervals in excess of 12 months are often caused by nutritional stress on the cow at some point either before the calving season or during the subsequent breeding season. This results in thin body condition and poor reproductive performance. The relationship of body condition to calving interval is shown in Figure 2. The thinnest cows have the longest calving intervals while fatter cows have shorter calving intervals. Producers should evaluate their cows for condition and apply appropriate supplemental feeding practices to correct nutritional deficiencies which are indicated when cows become thin. These deficiencies must be corrected or reproductive efficiency will remain low for cows in thin body condition.

Critical BCS

Groups of cows with an average BCS of 4 or less at calving and during breeding will have poor reproductive performance conpared to groups averaging 5 or above. Individual cows may deviate from the relationships established for groups; however, the relationship is well documented for herd averages. Body condition scores of 5 or more ensure high pregnancy rates, provided other factors such as disease, etc., are not influencing conception rates. It is acceptable for cows calving regularly to obtain a score of 7 or more through normal grazing, but buying feed to produce these high condition scores is uneconomical and not necessary.

It is desirable to maintain cows at a BCS of 5 or more through breeding. This implies that cows scoring less than 5 at calving need to be fed to improve their condition through breeding, which is expensive to accomplish while they are nursing calves. If cows scoring 5 or less lose condition from calving to breeding, pregnancy rates will be reduced. Cows scoring 7 or 8 can probably lose some condition and still breed well provided they do not lose enough to bring their score below 5.

An efficient way to utilize BCS involves sorting cows by condition 90 to 100 days prior to calving. Feed each group to have condition scores of 5 to 7 at calving. These would be logical scores for achieving maximum reproductive performance while holding supplemental feed costs to a minimum.

Supplemental Feeding Based on BCS

Regular use of BCS will help evaluate the body composition or fatness of cattle in a fairly accurate and rather easy manner. Cows which score 5 or more and still have reproductive problems likely have a mineral or vitamin deficiency, disease or genetic problem, or the problem may exist with the bull. Cows scoring less than 5 may not be receiving adequate levels of energy (total feed with reasonable quality) and protein, although other factors such as phosphorus and internal parasites may be involved. A combination of these nutritional problems is frequently observed.

In a commercial cow-calf program, the digestible energy requirement of the cow and calf should come from forage produced on the operator’s farm or ranch. Purchasing large amounts of energy supplements on a regular basis is not economically feasible. A cow’s energy deficit periods must be satisfied from body stores established during periods of forage surplus. Protein, mineral and vitamin supplements facilitate this process efficiently from both a biological and economical basis. The higher sale value of purebred cattle can make replacement of forage-energy with grain-energy economically feasible and often necessary for extra condition and marketing or sales appeal. Purebred breeders need to remember that their cattle should fit the production environment of their commercial customers, minimizing grain input, if they expect repeat sales.

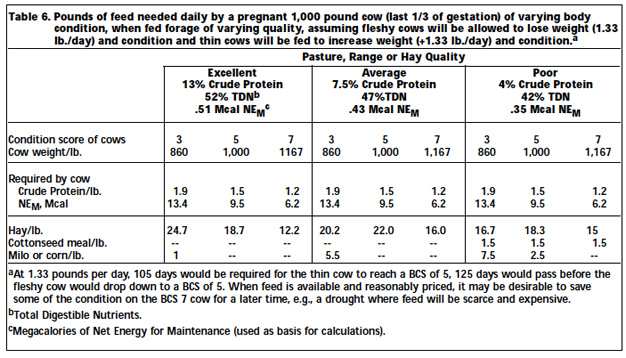

Numerous supplemental feeds are available in a variety of different forms. None of the supplements are best suited for all situations. The body condition of the cow, lactation status and quality of forage are major factors to consider in choosing a supplement. The influence these factors have on supplementation requirements is illustrated in Tables 6 and 7 for a cow that weighs 1,000 pounds at BCS 5. Producers should remember that other factors also influence nutritional requirements, such as weight, mature size, breed type, milk production level, travel and environmental stresses.

Body condition significantly alters the requirement for supplemental energy and slightly alters the need for supplemental protein, but it is not a determining factor of mineral or vitamin supplementation. Mineral supplementation with emphasis on salt, phosphorus, magnesium, copper, zinc and calcium is advisable in all situations. Vitamin A supplementation may not be needed with excellent forage, unless it is hay stored for a lengthy period. Vitamin A should be supplemented, especially for lactating cows, with lower quality forages regardless of body condition.

All cattle, fat or thin, need protein supplementation to consume and utilize low quality forage with any degree of effectiveness. Protein supplementation is recommended with low quality forage regardless of the BCS or lactation status of the cow. The efficiency of response to protein supplementation is normally greater than that to energy.

There are limits, however, to the improvement in animal performance that can be achieved with protein supplementation. if protein supplementation will not result in satisfactory performance, large amounts of grain-based supplements (including protein) must be fed or a better forage must be used. Whether energy supplementation or grain feeding is necessary depends largely on the lactation status and BCS of the cows and the quality of forage. Grain feeding is recommended only as a last resort since it is normally expensive and has negative associative effects on the efficiency with which cattle utilize forage. The depressing effect of grain feeding on forage digestion is greatest when large amounts are fed infrequently. Depressing effects result from reductions in rumen pH, changes in the rumen microbes and antagonistic alterations in the rate of passage of each feed through the digestive tract. Where energy supplementation is necessary in order to sustain a desired level of performance, provide small amounts at frequent intervals.

Protein and energy should be in proper balance. If protein is in excess compared to the level of energy, the excess protein will be used for energy. Although high protein feeds are good energy feeds, they are usuallly quite expensive sources of energy. Adding a high energy supplement to a forage that is deficient in protein will result in a total diet that is deficient in protein and poor utilization of total dietary energy. Timely use of energy in combination with protein supplements is often necessary with typical forage programs to properly develop replacement heifers and supplement heifers with their first calf. Mature cows should not need much energy supplementation on a routine basis.

Nutritional Management

Many cows in Texas need a higher level of condition at calving and breeding to improve reproductive performance and income. Grain feeding can be used to maintain or increase body condition, but this approach has economic limitations. Tables 6 and 7 illustrate that cows receiving higher quality forage require little or no grain supplementation, especially dry pregnant cows. Dry pregnant cows can utilize low quality forage without excessive grain supplementation. Cows with body condition scores of 6 to 8 can lose some condition without reducing performance and therefore need little, if any, grain.

With these points in mind, producers should choose a calving season that is compatible with their forage program, use a good mineral program which improves body condition year-round due to improved forage utilization, and consider protein supplementation whenever forage protein is less than 7 percent on a dry matter basis (e.g., summer drought pasture, mature frosted grass, etc.). Since protein supplementation stimulates the intake and digestion of low protein forage (<7 percent), body condition can be improved on droughty summer pasture and condition losses can be decreased on dormant winter pasture. This approach minimizes the amount and expense of energy supplementation, but may not eliminate it completely. Where minerals, vitamins and protein are furnished in adequate amounts, but body condition continues to decline, large amounts of energy supplementation will be required to stop further decline or to produce an improvement.

Because combinations of low quality forage and grain are used so inefficiently, it would be more eco- nomical to produce or buy a higher quality forage when high levels of animal performance are desired.

If the requirement for energy supplementation is a yearly necessity, a change in management is suggested. The supply of nutrients from forage must be increased, both in quality and quantity, or the nutritional requirements of the cattle must be reduced (cattle with less milk potential and probably smaller in size). The stocking rate of many herds needs to be reduced to allow a greater volume of forage for each animal thus reducing the need for so much supplement.

Summary

A BCS of 5 or more (at least 14 percent body fat) at calving and through breeding is required for good reproductive performance. Over-stocking pastures is a common cause of poor body condition and reproductive failure. Proper stocking, year-round mineral supplementation and timely use of protein supplements offer the greatest potential for economically improving body condition scores and rebreeding performance of beef cows in Texas. Sorting cows by condition 90 to 100 days ahead of calving and feeding so that all cows will calve with a BCS of 5 to 7 will maximize reproductive performance while holding supplemental feed costs to a minimum.

Nutritional and reproductive decisions, so important to profitability, are made with more precision and accuracy where a body condition scoring system is routinely used.